Let's pick up where we left off in Part I. If you missed it, check it out here.

If science is so awesome and facts are so perfect and incorruptible and truthful, then why do so many people think there isn't a scientific consensus about climate change?

Great question.

Though facts are objectively the truth as proven by science, you may have noticed that facts are sometimes assigned to a side, and in the process they get a bit bent out of shape, which is what I've been calling fact drift. The newly coined "alternative facts" also describes the phenomenon very well, though it's a darker, scarier, deliberate form of drift. More like fact shove down the stairs.

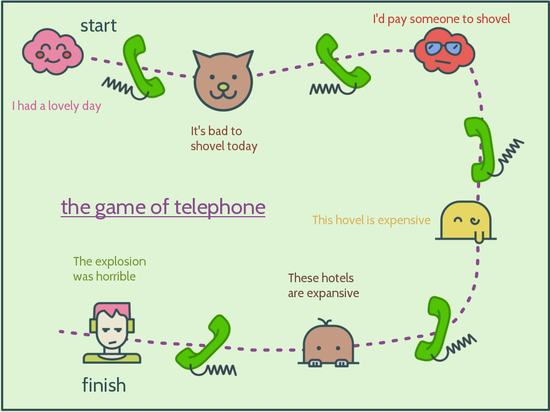

Fact drift isn't always malicious, though. Even when people have good intentions, the ways in which we receive our information can turn into a game of telephone.

If science is so awesome and facts are so perfect and incorruptible and truthful, then why do so many people think there isn't a scientific consensus about climate change?

Great question.

Though facts are objectively the truth as proven by science, you may have noticed that facts are sometimes assigned to a side, and in the process they get a bit bent out of shape, which is what I've been calling fact drift. The newly coined "alternative facts" also describes the phenomenon very well, though it's a darker, scarier, deliberate form of drift. More like fact shove down the stairs.

Fact drift isn't always malicious, though. Even when people have good intentions, the ways in which we receive our information can turn into a game of telephone.

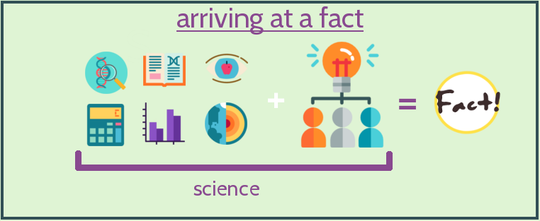

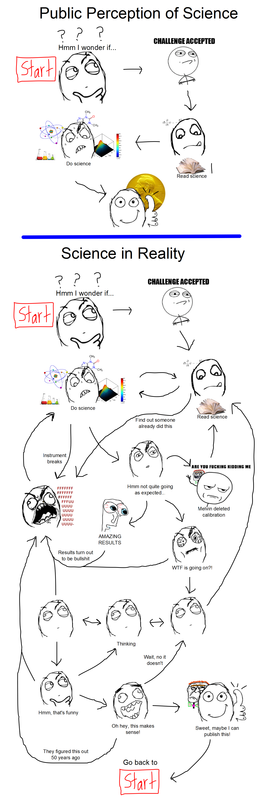

Moreover, unlike history or art or psychology or really any other discipline, science can be proven, which means it has one side--the correct side. For example, the theory of gravity, which has withstood the tests of time, scrutiny, and repeated examination, isn't open to interpretation, or at least not in the same way as a Jackson Pollock painting. But, it's easy to forget science's uniqueness and instead of reporting *the side* of science, filter its results through the same "on one hand/on the other" lens as everything else.

What might that filtering look like? How do facts start drifting? The journey might go something like this:

What might that filtering look like? How do facts start drifting? The journey might go something like this:

Row, row, row your fact, gently down the stream

1.) The scientific community arrives at a fact. Their science is sound, other scientists successfully replicated their experiment, and the conclusion they reached received wide acceptance by other members of the scientific community.

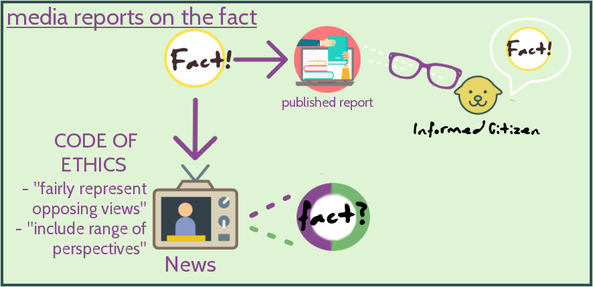

2.) The media report the findings. Because journalists are supposed to present all sides of a story, they’ll include the fact, but also include information that would potentially disprove the fact, even if there is no evidence of that information, or only non-experts disagree with the fact. When this happens, the amount of consensus and disagreement can be portrayed as equal, which is not the case.

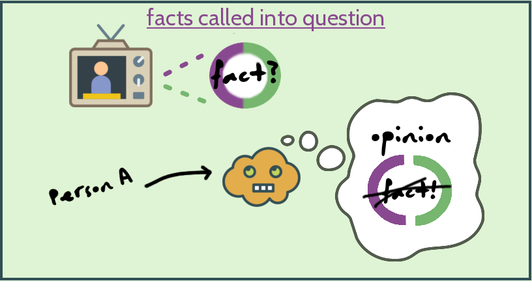

3.) Person A sees the media report that presents both sides of the story: the fact, and the apparent disproval of the fact. Because consensus and disagreement are portrayed as equal, Person A assume that the fact isn’t a fact.

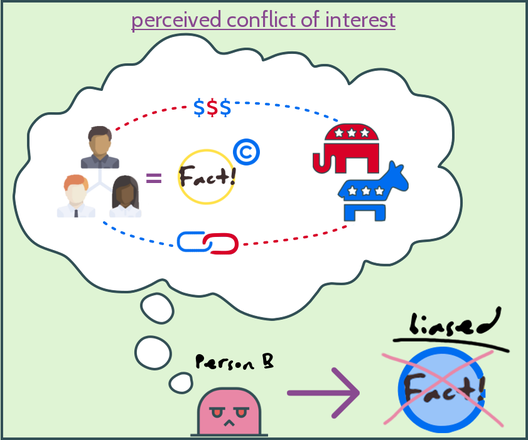

3a.) Person B may question the validity of the fact because the researchers who verified the fact operate on grant funds, and unless researchers “discover” a problem that requires more study, their funding will dry up. Person B thinks that conflict of interest—the pressure to falsify results in order to survive financially-- makes the fact inadmissible.

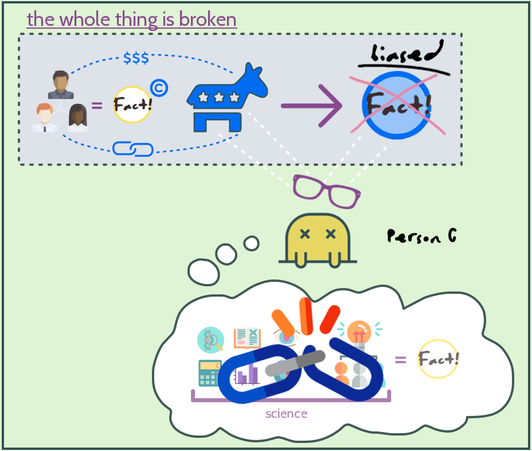

3b.) Person C claims that the conflict of interest not only negates the fact, but is also proof that on a whole, the scientific method is unreliable. The fact takes on a new identity as a representative of an imperfect and corrupt process.

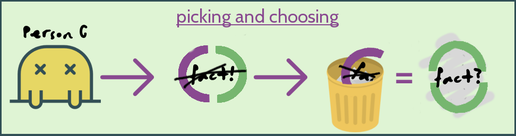

4.) Person C takes the media’s reporting, discards the fact, and propagates the contrary view offered because it more closely aligns with their personal opinion.

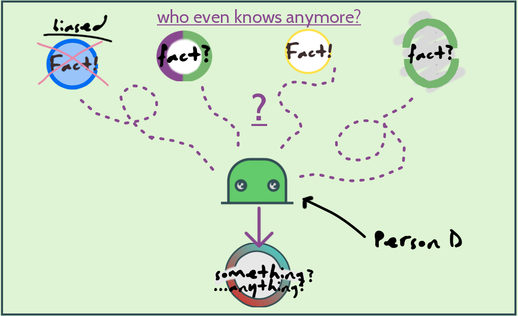

5.) Person D is confused as hell, and chooses whichever piece of the perverted fact best suits their personal beliefs.

Well HECK. What do we do now?

The above scenario (which, by the way, is one of the most straightforward and least Machiavellian of any of the ways in which facts drift or become "alternative") is problematic for many reasons; in my opinion, the two biggest, however, are that it undermines the validity of the scientific process and it keeps people from having all the information they need to make well-informed choices.

Now we know what's happening; how do we solve it?

Look at the "media reports on the fact" panel. You see the wee little "informed citizen" off to the right? That person (dog?) circumvented this whole trickle-down telephone game by going directly to the published report and getting their facts from the source. That fix is the most time-intensive, but it's also the most straightforward and reliable.

If you don't have time to pour through scientific journals, then the next step is to audit your news sources for potential bias. I think everyone (EVERYONE!) would benefit from reading/watching news and opinions from a variety of places, and allowing themselves to experience discomfort. I get extremely uncomfortable when I see things that defame science or condemn one of my strongly held beliefs, but I try very hard to look at why it makes me uncomfortable--is it because what they're saying is incorrect, or is it because I want what they're saying to be incorrect? If it's the latter, I have work to do.

On the most basic, basement level, the solution is still, always, endlessly, to ask questions, of yourself, of what you see, and of what's presented to you. Bring out your inner scientist and cultivate that inquisitive voice in others, so that facts stay right where they're supposed to be: rooted in objectivity as the result of a scientific process.

Next time: Finally, we get to the point. Part III-- the science of climate change.

Now we know what's happening; how do we solve it?

Look at the "media reports on the fact" panel. You see the wee little "informed citizen" off to the right? That person (dog?) circumvented this whole trickle-down telephone game by going directly to the published report and getting their facts from the source. That fix is the most time-intensive, but it's also the most straightforward and reliable.

If you don't have time to pour through scientific journals, then the next step is to audit your news sources for potential bias. I think everyone (EVERYONE!) would benefit from reading/watching news and opinions from a variety of places, and allowing themselves to experience discomfort. I get extremely uncomfortable when I see things that defame science or condemn one of my strongly held beliefs, but I try very hard to look at why it makes me uncomfortable--is it because what they're saying is incorrect, or is it because I want what they're saying to be incorrect? If it's the latter, I have work to do.

On the most basic, basement level, the solution is still, always, endlessly, to ask questions, of yourself, of what you see, and of what's presented to you. Bring out your inner scientist and cultivate that inquisitive voice in others, so that facts stay right where they're supposed to be: rooted in objectivity as the result of a scientific process.

Next time: Finally, we get to the point. Part III-- the science of climate change.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed